Arab control, and rule from Muscat – the 1800s

After Persian invasion and almost a century of internal conflict, the old Ya’rubid dynasty in Oman lost control to the Al Bu Sa’idis. But all such wrangling for power had wider consequences on the East African Coastline, where the smaller dominions of the same parties were fighting parallel battles, and often resulting in differing outcomes. The rising regime in East Africa was the Mazrui dynasty, whose allegiance to Muscat had become tenuous following the rise to power of the Al Bu’Saidi clan, to whom they were opposed. The Mazruis had gained authority in Mombassa when they were appointed governors there by the Imam of Oman in 1698, and continued to manage the volatile situation there until the early 1800s, by which time they successfully dominated a large region extending to the Pangani River in present day Tanzania.

But further south allegiance tended towards the Al Bu’Saidi Sultan of Muscat, especially from Zanzibar and Kilwa, which was once more rising to prominence. The island state reinstated trade with the interior, and thrived especially on imports of cloth, arms, ammunition and salt, and exports of ivory, until around 1730, when they increased the export of slaves, especially to French colonies such as Mauritius and Reunion where they would work on the sugar plantations.

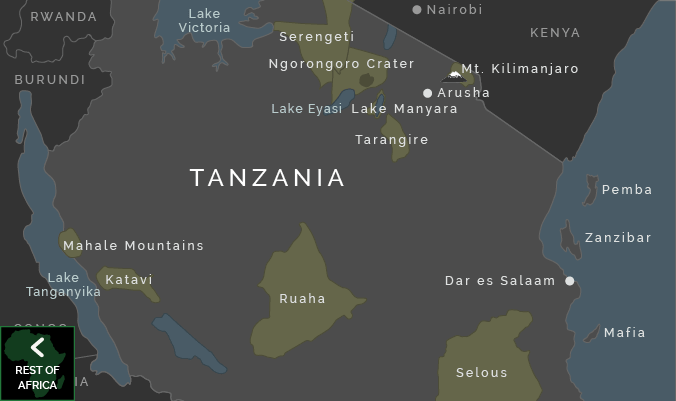

The Sultan of Muscat was now fully awakened to possible economic interest in the area, and he appointed a new Omani governor of Kilwa in 1784. Their navy developed greater power along the coast, and took Zanzibar as their central stronghold. He masterminded the annex of Pemba in 1822, and finally Mombassa in 1837. It was perfect timing with regards to export profits, especially for ivory, which continued to earn greater demand; between 1820 and 1850 the price of ivory doubled, then trebled again by 1890. It was exported to the west, for knife handles and piano keys, but mainly to India for ivory bangles that would then be burnt with the woman when she died.

Strengthening trade routes and the changing coastal kingdoms

The blossoming Arabic trading network had relied heavily on the co-operation of tribes in the more inaccessible reaches of the interior, and consequently increased economic wealth throughout Azania. The vast interior had gradually shaped into a complex network of tribal or clan strongholds between the lakes of Victoria, Albert, and Tanganyika dating from before the middle of the second millennium AD, although historical records of the details are scarce. Thus it is hard to fully establish the origins of these rulers, although it is likely that they had a connection with the immigrating Cushitic or Nilotic people from the North. These first chiefdoms either spread or developed independently around Southern regions of Tanzania at around this same time, and accounts tell of around 200 small chiefdoms led by a tribal chief, known as ‘Ntemi’, each served by a council over about 1000 subjects. These ‘kingdoms’ developed in response to population growth and the need for greater political control beyond family ties, as was previously traditional. Later, in the case of the Kilindi kingdom in the Usambaras, a stronger political system became a necessary defence against the influx of warrior-like migrating tribes, such as the Maasai. The changing nature of trade also affected small, inland communities, as the availability of firearms at the coast forced them to join with larger groups for protection against slave raids.

Chiefs of tribes in the interior, such as Fundikira of the Nyamwezi around Tabora, the central Tanzanian Gogo, and Yao chiefs from Kilwa seized the opportunities opened to them by the acceleration of foreign trade. Over the course of centuries these made a reputation for themselves by organising their people as porters and traders, carrying goods over many hundreds of foot miles and earning themselves notoriety and relative wealth; although real wealth was limited by the greater economic control of the coastal traders, who kept the lion’s share for themselves. Inland tribes also capitalised on the trade routes by starting to demand ‘hongo’, a toll or a tax on the caravans for passing through their territories. By the mid-1800s, the interior had evolved into a small number of larger tribal empires around centralised, fortified villages.

Resistance to Arab control

African chiefs attempted resistance to Arab control, or otherwise sought to capitalise on the riches passing by them. The great chief Mirambo (ruling just west of Tabora, which developed as a permanent Arab stronghold and collection point towards the end of the 19th century), famously built a fortified empire in the middle of the trade routes, only allowing them through after paying tributes. He successfully united the numerous Nyamwezi clans into one powerful kingdom from around 1850, and led military missions to make alliances with all his neighbouring chiefs and clans in the east, south, north and west. His incredible resourcefulness and drive earned him the nickname the ‘ Napoleon of East Africa’, coined by the journalist Henry Morton Stanley. His empire thrived for the couple of decades through the 1860s, ‘70s and early ‘80s, but diminished after his death in 1884.

Arab traders had begun to venture along the extended caravan tracks penetrating the interior in the mid 19th century, but they were mainly focused on their growing trade settlements along the coast, and tended to rely on the existing tribal networks and inland systems to bring them their required resources. This focus then established a division between coast and interior that would develop and grow over successive years.

By the end of the 1800s ivory was becoming scarce through the interior, and arms and ammunition more widespread.

A Coastal Language of Trade and Exchange

The organic growth of Arabic trade settlements along the coast and islands – either long term settlers or traders waiting up to six months for the monsoon winds to turn about, and bear them back to the Gulf – required such a close integration of Arabic and Bantu that there evolved a shared coastal language, a working, growing language of trade and exchange, called Swahili, (from the Arabic word Sahil, meaning coast). Even the name of this fundamentally Bantu language expresses something of its curious nature, which is constantly and eclectically influenced by the external cultures which affect it. The language was developed as a common means of exchange all along the coast, and incorporated Arabic words either in preference over the similar Bantu phrase, such as Sahil, (the Swahili word for coastline is ‘pwani’), or where there was no word to describe the foreign imports already.

During the 19th century the Swahili language was carried along the inland states by the caravan trade and so was more widespread among the different tribes. This made it the ideal choice when the British colonial government sought to unify the disparate territory of Tanganyika, and later when the fundamentally socialist policy of ‘Ujamaa’ was introduced in the mid-seventies and a shared language was required to carry the message to all the different tribes in the new nation. The differentiation of tribes was to be consciously eroded so that the country may be united, and there was an active parliamentary push to publicise Swahili as a political language to achieve this goal. The actual success of the spread of Swahili throughout East Africa has since inspired a greater incentive to encourage and teach Swahili as the uniting Lingua Franca of the African continent.

Sutan Said

Seyyid Said Sultan bin Sultan of Oman ruled the East Coast from Zanzibar for 50 years after signing a treaty with the chief of the Zanzibari Hadimu Chief, the Mwinyi Mkuu, to colonise the island in 1828. His shrewd business sense ensured that the Omanis took the best land on the Western side of the island, leaving the less fertile stretch to the east for the Hadimu, and he pushed and encouraged his subjects to exploit all possible economic openings and trade possibilities, especially slaves and ivory, which achieved international renown. He saw immediate potential in clove plantations, first brought to the island in 1813, and insisted that all of his subjects planted cloves alongside their coconut trees. His domain soon rivalled the power of Mombassa as a focal point for international trade, and by 1837 he spotted a weakness in the Mazrui stronghold in Mombassa and thus extended his stronghold along the entirety of the East African coastline. The Sultan developed a stronghold of power based on trade, and in 1840 he transferred the seat of his rule to the sunnier, more profitable climes of Zanzibar.

India had traded with Zanzibar and the mainland coast for centuries, but the excellent terms encouraged by the Sultan inspired greater numbers of Indian merchant settlers on Zanzibar, escalating from a small population of around 215 in 1810 to at least 5,000 fifty years later. They began providing credit for goods, finance expeditions into the interior and acquired the right to collect taxes on behalf of the Sultan. From 1827, the Indian merchant family of Jairam Sewji rose to prominence alongside the Sultan as the wealthiest and most powerful in Zanzibar. This later created the loophole through which the British slipped to limit the power of the Sultan and intervene in the Zanzibari trading laws, as the Indian merchants could technically be recognised as citizens of British India.

Sultan Said was already familiar with negotiating with the British long before he settled in Zanzibar, as he had turned to them for assistance while establishing his authority in Muscat, and they had happily provided it in return for safeguarding their trade routes to India. But the first Europeans to secure contracts with the Sultan on the flourishing African settlements were the Americans, who spotted the potential for trade and negotiated a deal in 1833, then established the first consul four years later. Their supply of cheap cotton cloth was so successful that any such material became known as Americani. The British devised their trade agreement with the Sultan in 1839, and their consul in 1841, followed by the French and Germans. The international interest provoked a wider range of items for trade and exchange, and made diluted the Sultan’s ability to withstand pressure to curtail the slave trade. The British had begun this in 1822 when they drew up the Moresby Treaty, to end the trade of slaves to any predominantly Christian country, and in 1845 the Hammerton Treaty attempted to ban the slave trade to Muslim territories too, although the British only succeeded in finally closing the slave market in Zanzibar many years later, during the reign of Sultan Barghash in 1873.

Missionaries and Explorers

In the mid-ninteenth century, the first European missionaries with a will to convert East African pagans were forced to be explorers too, and discovered areas of the interior still considered to be ‘unknown parts’ by western geographers and scientists. Among the first successful expeditions to be made were those by Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann to the Chagga lands around Kilimanjaro on behalf of The Christian Mission Society. Rebmann reported back to British shores that he had witnessed a snow-covered peak on this unusual equatorial mountain. His report reached the National Geographic Society, and was promptly dismissed as being mad rantings of an unhinged mind. The map of the lakes in the northern regions produced by their fellow missionary Jakob Erhardt, admittedly on the basis of reports from Arab traders along the caravan routes, showed a large body of water that was probably Lakes Victoria, Albert and Tanganyika all running into one. This large blob of water earned the drawing the name of ‘the slug map’, but nevertheless incited the great geographers to ascertain the truth for themselves. Worthy explorers were duly found, and despatched to the shores of Africa to decipher the truth from the missionaries’ reports.

Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke set off from Bagamoyo in 1857, and endured harsh adventures through the interior with the primary directive to determine the source of the Nile. Leaving Burton sick near Tabora, Speke reached Lake Victoria alone, and propounded his theories about the Nile source, and returned in 1860 in an attempt to verify them, this time in the company of J.A Gant.

The Scottish missionary, Dr David Livingstone, incentivised by his work as a missionary and his abhorrence of the slave trade that he sought to end, also became increasingly fascinated with establishing the Nile source as his journeys unearthed geographical discoveries. Livingstone made his last journey to Lake Nyasa in 1866, and in his wake journalist Henry Morton Stanley, attracted less by geography and more by the kudos and intrigue of discovering the whereabouts of the now famous missionary, whose disappearance on the Dark Continent was causing great concern at home.

A number of Christian missions were then inspired to brave the wilds of the African continent during this period between the mid to late 1800s. The Roman Catholic missionaries arrived in Zanzibar in 1860, and settled in Bagamoyo in 1868, and were followed by Anglo-Catholic, Anglican, and Catholic White Fathers, who worked their way along the trade routes emanating from Zanzibar and Bagamoyo through Tabora to Lake Tanganyika.

Tribal movement and change

But life among the fiefdoms of the interior continued to evolve, especially as developing agricultural abilities increased populations in fertile regions, and external tribes continued to move in. The forced and necessary migration and interaction of many different peoples encouraged wider forms of trade, but also displaced smaller tribes and resulted in widespread in-fighting and contention. During the 1800s, warrior-like tribes such as the nomadic Maasai moved south into the foothills of Mount Meru in the North, and the south was prey to fairly constant attacks from the Ngoni tribe, and the Ngindo, Mwera and Makonde. These southern counterparts were forced northwards by the fighting prowess of the southern African Zulu tribe, had also learned a few tricks for survival and attack. As a result, settlements became increasingly adept at defending their settlements, and when, the first German Europeans ventured inland during the late 1880s, they found that ‘everywhere people had withdrawn to fortified villages, and concluded that the land was freely available for European settlement’.

German intervention – 1885 onwards

During the mid 19th century, the German ‘Iron Chancellor’ Bismark employed an aggressive colonial policy of expansion. German imperialism took a hold on the realisation that although the Sultan of Muscat claimed nominal hold over the lands of the interior, he was a world apart from the African Chiefs who actually ruled their peoples in these wild and often distant lands. The Sultan cared only for the fruit of the caravan trails, with little real administration or care for the land otherwise.

So young German imperialists with dreams of colonial expansion, such as Carl Peters and his colleagues Joachim, Count Pfeil and Karl Juhlke devised an impudent trick that would allocate them the land they desired. They simply avoided the Sultan’s coastal ports and ventured directly into the mainland bush, where they signed twelve treaties with individual chiefs who were persuaded to give their territories to these strange newcomers with their unusually pale skin.

(The word Mzungu literally translates as ‘he who goes around’, (ie travels/ moves around) although it is unknown when this word was first employed to describe the white man, but seems fitting enough from the first.)

The treaties mainly concerned land that was actually already the Sultan’s domain, but when Bismark ordered five warships to sit along the shores of Zanzibar, the Sultan was persuaded to accept the German purchase offer of 400,000 marks for land along the coast.

Peters organised further expeditions pushed inland through 1880s, following the trade routes established by Arab slave trade and Nyamwezi commercial trade caravans, and in 1885 Bismark claimed a central portion of the interior as a German protectorate, under the rule of The German East Africa Company, headed by Carl Peters. But the strength of resistance from all the different tribes resulted in extensive military response, requiring the assistance of the army by 1889 and earning Peters the Swahili epithet ‘Mkono wa damu’, ‘Him with blood-stained hands’.

By 1890, the protectorate was extended as far as Mwanza and Bukoba. In this year the British and Germans began establishing the boundaries of German East Africa, which included present-day mainland Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi.

Resistance to German control

Between the years of 1888 and 1896 fifty four military conflicts were recorded in resistance against the colonial control. The first rebellion in 1888, described by Germans as the ‘Arab Rebellion’, began on the coast, led by Bushiri bin Salim (enemy of Sultan Said) and Zigua chief Bwana Heri (who had resisted Omani control of Sadani). Between them they amassed widespread support, as Bushiri rounded up supporters on the coast and Bwana Heri came close to uniting the inland tribes. They initially overcame the superior force of the German firearms by engaging in guerrilla tactics, mainly ambush from the bush, but the German troops responded with a terrifying ‘scorched earth’ policy in which they burnt crops and crop stores, destroyed villages and confiscated cattle. By 1889 Germans triumphed, under the military control of Colonel Wissman. When Bwana Heri surrendered as a result of widespread hunger and famine in 1890, he was followed by troops of Zigua people, Nyamwezi, Arabs, Indians, and slaves. The Nyamwezi chief, called Siki, blew himself up in his ammunition store to evade capture from the Germans when they besieged his fortress near Tabora, and Chief Mkwawa of the Hehe put a bullet through his own skull when his options ran out.

Chief Mkwawa and the Hehe

The German troops met with considerable resistance in the Southern Highlands, where the Hehe tribe had formed a military state around an impressive central fortress, under the formidable warrior Chief Mkwawa. The Hehe had been more or less forced to adopt a military strategy in response to influx of the Ngoni tribe from Southern Africa, who were themselves being squeezed north by the Zulu despite their favouring a strict military regimental system and good use of Zulu-like spears. The resultant clash around the Iringa plateau brought about the need for unification of the tribes, and also the emergence of strong leaders, such as Munyigumba and his son Mkwawa, who led the tribe successfully through a violent five year war with the Ngoni, between 1878 and ‘82 and sent the Ngoni east of lake Malawi. So when a German Military expedition met with Mkwawa’s troops in 1891 they unwittingly faced a highly organised military system and suffered the consequences; the Hehe were rumoured to have taken only 15 minutes to kill 290 members of the colonial forces.

Three years later the Europeans had their revenge, and put a garrison commander in Iringa. They pounded Mkwawa’s fort with grenades, and overcame the tribe by force of their far superior firepower. Mkwawa, however, escaped, and having evaded capture for for four long years, he famously refused to be taken alive and instead took his own life.