Almost all of the many attractions of Tanzania today are linked – in one way or another – to this country’s extraordinarily rich and diverse history. This East African land has evolved through centuries of change; the gradual migration and settlement of over one hundred and twenty different tribes, the intervention of foreign merchants and explorers, years of colonial masters with their politics and wars, and finally independence, self-governance and international tourism.

The greatest part of the known history of mainland Tanzania has been pieced together from the oral tradition of tribal story-telling, explorers’ tales and archaeological remains, although written records exist dating back to the 1st century AD describing trade and lifestyles on the islands and coastal regions. Fossil evidence has also been found of life many thousands of years earlier, including some of the earliest known evidence of proto-human ancestors, various types of hominid, which earned Tanzania the strange accolade of perhaps being ‘The Cradle of Mankind’.

Pre-history

Africa is geographically ancient. This vast and diverse continent is thought to have once been a major component of the Gondwanaland supercontinent that drifted apart in the Mesozoic period, 150 – 100 million years ago. The ancient rock strata of Tanzania have retained a historical record of buried evidence, only now partially revealed by time and science. Petrified dinosaurs, such as the giant Brachiosaurus and tiny Kentrosaurus, were found on Tendaguru mountain in the region of Lindi in southeast Tanzania in 1912, (now removed to the Natural Museum of Humboldt), and one of the oldest known examples of bipedal hominids, immortalised in a set of fossilised footprints, were found at Olduvai Gorge in Northern Tanzania. Many more remains have been unearthed dating from the Stone Age, between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago, in regions throughout Tanzania, (such as the excavation site and museum at the Stone Age site at Isimila, in the Mbeya region).

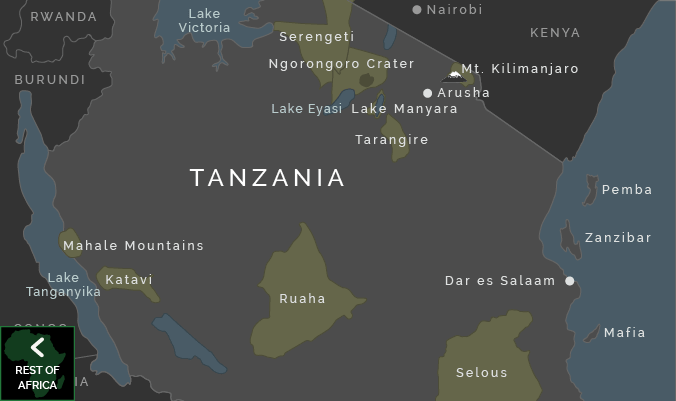

It is thought likely that these earliest civilisations could be direct ancestors of the bushmen tribes still (just) in evidence in Tanzania today, notably the remaining Hadzabe tribe, now clustered around Lake Eyasi, west of the Serengeti. In those ancient days, the hunter-gatherers had the run of the land, but soon their freedom was to be curbed and their tribal centres displaced by migrations of other tribes displaced from surrounding lands. In tribute to their ancient civilisation, they left a legacy of rock paintings, covering over a thousand sites. The best of these can be seen at Kondoa in Kola, Cheke and Kisese.

A steady migration of peoples

From around 1,000 BC, pastoral and agricultural Cushitic-speakers from North-western regions around Ethiopia & Somalia began migrating southwards into the expanse of land beyond the Azania coast, as this coastal region was now becoming known. These early pastoralists were responsible for the first instances of food production in Tanzania, and have left evidence of their cattle herding and irrigation techniques, perhaps including the advanced systems that have been excavated at Engakura. The Iraqw people of Northern Tanzania and the Mbulu, Burungi and Gorowa are likely to be the descendants of these early Cushitic immigrants.

This era saw the emergence of the Iron Age in Tanzania around this time, which first spread across the Northern reaches of the interior. The most important Iron Age sites are those around Lake Victoria, notably the site of Urewe in the Kagera region, from where techniques used to create hard-wearing and distinctive ironwork pottery later spread throughout East and Southern Africa. Other Iron Age tools and hand-axes were also found in abundance at Isimila near Iringa, and Katuruka, near Bukoba. The Cushitic tribes were joined a short time later, around 500 AD, by different tribes of Bantu-speaking people who slowly moved in, by various routes, from the direction of West Africa, and in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD there came an influx of pastoral Nilotic tribes into the north-western regions.

The influx of migratory tribes has continued through the years until recent times, with such renowned inhabitants as the Nilotic Maasai tribe arriving for the first time during the 1800s, cutting a fearsome swathe through the northern reaches of Tanzania from Kenya, raiding cows, women and land from the tribes in their path. Their southerly progress was thwarted north of Dodoma, at the centre of the country, by a combination of sickness and untimely combat with the Hehe tribe. All migrating clans also found their free progress of movement through the interior occasionally impeded by the notorious tsetse fly, which, apart from an unpleasant stinging bite, can also carry the sleeping sickness trypanosomiasis, (this is correct spelling) which threatens the lives of domestic animals and can badly affect people. Wide areas of land were avoided and uninhabited as a direct result of the tsetse fly belts, and the same remains true today, although their numbers have been significantly limited.

Assimilation and interaction

The attraction of this wild and uncharted expanse of land encouraged displaced tribes from North and West Africa to settle here, for reasons of war, famine, disease, drought and pastures new. As different tribes and clans moved they were absorbed into other clans or otherwise divided, or they were forced to move on by the arrival of newcomers, or displaced other peoples. This slow and constant ebb and flow of life encouraged new forms of trade, as each group brought with them new skills, ideas and foodstuffs, and developed a barter economy based on goods produced, grown or acquired from one region to the next. The most valuable of these, notably salt, iron hoes and livestock, eventually became a form of currency, and a network of trading paths thousands of miles long developed in response to demand for items between the interior and the coast.

And sailors to the shores

Then came the first wave of foreigners arriving by sea, keen to pay for exotic ornamental and aromatic goods that were not necessities for life in Africa, but would provide them in plenty in exchange. Evidence of these early sailing ventures is carved into stone monuments of the Ancient Egyptians, who navigated the Horn of Africa and later continued further southwards in their desire to trade for incense and myrrh to use in their spiritual ceremonies, and ivory, tortoiseshell, ebony, ambergris, and palm oils. Their ancient carvings give some indication of the attractive wealth of resources perceived to be abundantly available from the coastline of East Africa, and include many items that have continued to draw sailors to these shores for at least four millennia since.

The Temple of Thebes at Karnak celebrates a man named Seneb from the Land of Punt, whose memory was inscribed in about 2050 BC. The hieroglyphics for Punt can be translated as ‘shoreline’ or ‘coast’, and may refer to the East African coastline, although mainly to Somalia, probably known to Ancient Egyptian civilisations for its exotic fragrances for a thousand years even before the days of Seneb. Subsequent journeys were organised by Queen Hashepsut, whose temple at Deir el-Bahri near Luxor tells of the ships that she sent to Punt in 1493BC, showing shiploads of her rich rewards, as well as depicting fish and fauna that the expedition discovered. Herodotus records an impressively successful mission in 600BC, initiated by King Necho II, who sent Phoenician sailors across the Red Sea and down the coast of Africa, to return three years later through the Strait of Gibraltar (‘the Pillars of Hercules’) and back Egypt via the Mediterranean.

Influence of Arabia, blown to Azania on the monsoon winds.

One of the earliest written records of this East African shore was Ptolemy’s ‘Guide to Geography’, which described the extent of world knowledge in Byzantium in around 400 AD. This refers to an offshore island called Menouthias in the Indian Ocean which may have been Mafia Island, or either Zanzibar, Pemba, or a combination of all three.

Trade routes to the region were so established by the latter end of the 1st century that they then featured as the focal point of a ‘guidebook’ scribed at this time, which provided a detailed and lengthy account of foreign trade along this Indian Ocean shoreline. The work was titled Periplus Maris Erythraei, ‘Periplus of the Erythraen Sea’, (now the Indian Ocean), and was compiled by a Greek merchant living in Egypt. His account describes a thriving trade capital of Azania called Rhapta, with clear geographical references that place it in the middle of the present Tanzanian coastline. But no remains of this centre have ever been discovered in the modern world, and scholars believe that it may have been subsumed by the vast and changing silt flats of the Rufiji River Delta.

This growing geographical awareness and the abundance of natural goods also attracted another, more distant civilisation from the Eastern shores of the Indian Ocean during the early years of the 1st century AD. At this time, maritime expertise had developed enough to trust sailors to the monsoon winds, which blew their wooden crafts to the shores of Azania from the Arabian Gulf. By 700 AD, the Arabian merchants of the wind-borne trade routes began to truly appreciate the benefits of the offshore islands, numerous landing places and wetter climate of the Azania coastline, and to shift the focus of their trade southwards from the coast of Somalia. They arrived with cargoes of copper, tin, cloaks and cloth, daggers, hatchets and glass, and exchanged them for aromatic gums, coconut oil, tortoiseshell, ivory and slaves.

In the way of all explorers, these early sailors also sought to record their findings, and early Arab geographers described the coast as ‘Zanj’, Arabic for ‘Black’. Archaeological evidence suggests that the first significant migration to the islands of Zanzibar occurred around 750 AD, which concurs with historical records of political and religious strife in the Persian and Arabian Gulf at this time. Entire families took up their belongings and re-located to the more pleasant palm-fringed climes of Zanj. It is likely the majority of these migrants followed the ancient Zoroastrian faith, as they were suffering persecution in Persia as a result of the rise of Islam, and migrated to all regions of the then known world in response. But the majority of immigrants who chose to settle described themselves as Shirazi, and all determined to establish themselves as ruling Sheikhs, whether they were or not.

By the ninth century their records mention a civilisation existing on an island they called Quanbalu, now thought to have been present-day Pemba, where the Arabic inhabitants became rulers of the native pagan population. Islands were attractive to prospective settlers on account of their malleability, and the security that their position afforded against attack from the mainland. Settlements developed with a constant ebb and flow of population, as the eastern traders continued to flock to its shores whenever the monsoon winds would bear them across the Indian Ocean.

Development of the Gold Trade, and Swahili City States.

The centuries between 1200 and 1500AD saw Indian Ocean trade between East Africa, Persia, Oman, India and China reach an all-time high, and trading posts along the coast enjoyed lavish prosperity as a result. They exported ivory to India and China and mangrove poles to the Arabian Gulf for building houses, and tortoiseshell, leopard skins and ambergris, but the greatest wealth issued from the gold trade, which from 1200 AD began to follow an overland route from present day Zimbabwe to Sofala in present day Mozambique. It was then transferred up the East African coast by sea to Kilwa, and probably also to Rhapta, Mafia and Pemba. From these trading posts it was then exported to India and the Gulf, where it was exchanged for imported textiles and porcelain from China, the latter in such copious amounts that it was used to adorn and decorate the new East African buildings. The island of Kilwa developed as a central port because Arab dhows could not sail much further south to return on the monsoon winds. By the fifteenth century Kilwa had overtaken Mogadishu as the centre of the gold trade, and the population had grown to several thousand, a huge population for sub-Saharan Africa at the time. With its vast stone palaces, houses and mosques, the town became known as ‘the last outpost of the civilisation of Islaam’.

The advent of the Portuguese

But this increasingly lavish lifestyle was not without contenders, from other Arab settlements and native islands, and their prosperity rocked according to fortunes and fate.

Finally, at the very latter end of the 15th century the first European ships successfully navigated a sailing route around the Cape of Good Hope to discover these East African shores, captained by the notorious Portuguese sailor, Vasco de Gama. He docked in Malindi, on the Kenya coast in 1498. His travels had taken him past the islands and ports of Kilwa, Mafia and Zanzibar, and alerted him to the flourishing trading possibilities in gold, ivory, slaves and much else besides. He sent emissaries to Portugal for more boats and gun-power, and returned to force the Sheikh of Kilwa to bow to their sovereignty in 1502, to later sack the island in 1505, using the new gunboats to their great advantage. They went on to subjugate the island states of Zanzibar and Lamu and Pate in Kenya.

Their greatest stronghold was in Mombassa, where their garrison was housed within the walls of their Fort Jesus, and they undermined a number of the greater Shirazi dynasties and cowed the others with demands for regular tribute and payments, making clear that the alternative was dethroning and destruction. Their principle aim was trade and gain. They took the cream off every form of economic exchange within their asserted jurisdiction, and controlled the trade routes between the East African coast and India.

But such ascendancy did not go unchallenged, and although they could withstand smaller local rebellions they were less able to contend with changes of government and power in Arabia. The Persians took back Hormuz in 1622, and Imam of Oman took control of Muscat in 1650. In 1652 the Omanis sent ships to Zanzibar and Pate to rid the islands of their Portuguese incumbents, although the Europeans retained strongholds here, notably in Mombassa, until 1698, when Fort Jesus fell to the Imam, Sayf ibn Sultan. There was no lack of love lost between the different factions, and there followed a short period of respite along the East African coast while conflicts in the Gulf countries reshuffled ascendant powers.